WhatsApp is a communication platform that allows users to message each other – either via text, audio, or video.

WhatsApp makes money via fees from its Business API product as well as by imposing a transaction fee on WhatsApp Pay.

Founded in 2009, WhatsApp has grown to become the world’s largest communication platform. It is used by over 2 billion people in over 180 countries across the globe. Additionally, more than 100 billion messages are exchanged on its platform every day.

What Is WhatsApp?

WhatsApp is a messaging application that allows users to communicate with each other via text, audio, and video.

WhatsApp can be accessed via its tablet and smartphone apps (available on Android and iOS devices) as well as its web application (called WhatsApp Web).

Users can communicate with each other individually (in private chats) or via groups of up to 512 members.

WhatsApp’s platform is end-to-end encrypted, meaning that only the users in the chat can read the messages.

Apart from text messages, users can also exchange emojis, GIFs, audio messages, pictures, videos, and even share documents. They can, furthermore, react to text messages.

If users feel like sharing their special moments, they can do so via WhatsApp’s Stories feature. These moments are then displayed for 24 hours to anyone who saved the contact.

Apart from its consumer application, WhatsApp also offers a communication tool for businesses (named WhatsApp Business). Firms can:

- Set up business profiles with helpful information for their customers (such as an address, email addresses, or a link to their website)

- Labeling contacts for better categorization

- Automated messages and quick replies

- Broadcasts (similar to a newsletter)

The WhatsApp Business tool is geared toward small businesses. If a business has some greater scale, it can opt into using WhatsApp’s Business API. The API endpoint allows them to integrate it into their existing business software.

WhatsApp is used by more than 2 billion people in over 180 countries across the globe. As such, it is the world’s largest communication platform.

The History Of WhatsApp

WhatsApp, headquartered in Mountain View, California, was founded in 2009 by Jan Koum and Brian Acton.

Koum was born in Kyiv, Ukraine, during the 1970s. He spent the transformative years of his childhood in Fastiv, a small town just outside of the Ukrainian capital.

Being of Jewish descent, Koum and his family often became the subject of anti-Semitic behavior. On top of that, the Soviet government was notorious for spying on its citizen, leaving the family with no room for privacy to express the predicament they felt being in.

In 1992, at the age of 16, Koum and his mother were allowed to immigrate to the United States where they ended up in Mountain View. Unfortunately, his dad was never allowed to enter the country and eventually died in 1997.

The mother-son-duo spent their first few years in a small two-bedroom apartment provided via government assistance. To make ends meet, Koum’s mother took up a babysitting job while Jan worked as a grocery store clerk.

A few years later, his mom was diagnosed with cancer and they continued to live off of her disability allowance. By that time, Koum was already heads deep into computers. He became a self-taught programmer by purchasing manuals from used bookstores and returning them when he was done reading (to save money).

In the mid-1990s, he enrolled himself at San Jose State University to pursue a degree in Computer Science. Koum ended up joining Ernst & Young as a security tester post-graduation. In 1997, EY assigned him to work on Yahoo’s advertising system where he ended up meeting Acton.

Acton’s path prior to their meeting couldn’t have been more different. He was born and raised in Michigan where his mother ran a freight-shipping company, allowing them to live a fairly comfortable life.

He ended up doing his Computer Science undergrad at Stanford and then joined Apple as a software engineer. In 1996, Acton became Yahoo’s 44th employee where he quickly climbed the corporate ladder.

The pair hit it off immediately and Acton convinced Koum to apply for a role at Yahoo. 6 months later, Koum joined the internet giant as an infrastructure engineer. He even dropped out of college (he was still attending San Jose State at the time) to completely focus on Yahoo.

Their relationship deepened in the years that followed. When Koum’s mother died of cancer in 2000, Acton immediately offered his support. He’d frequently invite Koum over to his house, on skiing trips, or to ultimate Frisbee matches.

While their bond became stronger throughout the years, their dissatisfaction with working at Yahoo grew alongside it. The majority of their time at Yahoo was spent on releasing Project Panama, the firm’s long-awaited advertising platform.

In the end, having worked on an advertising product for almost a decade, both Acton and Koum felt emotionally drained. Their dislike for advertising products should eventually come back to haunt them, though (more on that later).

In 2007, a year after the launch of Project Panama, both Acton and Koum handed in their resignation. They embarked on a year-long hiatus, traveling around South America and enjoying games of ultimate Frisbee.

Then, around the beginning of 2009, Koum purchased his first-ever iPhone. He immediately realized that the App Store, which had just launched a few months prior, would spawn a whole new generation of businesses that would build on top of Apple’s ecosystem.

A mutual friend of Koum introduced him to Igor Solomennikov, a Russia-based iOS developer that would help him build the product’s frontend (while Koum was responsible for the backend portion).

A few weeks later, on February 24th, 2009 (which is also Koum’s birthday), he incorporated WhatsApp Inc. in California. WhatsApp, by the way, is short for “what’s up”, a phrase Koum found befitting for a messaging app.

Over the next months, Koum spent hours upon hours programming the app. Unfortunately, a plethora of bugs caused it to continuously crash. At one point, he was even ready to call it quits. Acton’s response was fairly blunt: “You’d be an idiot to quit now,” he stated. “Give it a few more months.”

Koum’s perseverance eventually paid off when Apple released push notifications in the summer of 2009. Each time one of the app’s users changed their status, all of their contacts would get a notification.

Eventually, people would start messaging each other through the app – from any place around the world. While this may sound dull in today’s hyper-connected world, WhatsApp’s introduction became a huge revelation and, for the first time, indicated the impact smartphones could have on our lives.

At the time, the only free texting application was BlackBerry’s BBM, which was solely accessible to users that owned a BlackBerry device. User growth started to snowball when Koum released an upgraded version of WhatsApp that included a messaging interface (i.e. chats). Over 250,000 users downloaded the app within a matter of days.

To keep up with demand, Koum came to see Acton, who at the time was still unemployed and working on another startup idea, to convince him to join the project on a full-time basis. When Acton used the app for the first time, he immediately realized the limitless potential that a messaging platform like WhatsApp could have.

A few months later, Acton was able to convince 5 of his former colleagues at Yahoo to invest $250,000 in the startup’s first-ever seed funding round. The funding round, furthermore, granted him co-founder status and a significant stake in the company.

The money allowed them to hire a few more developers that would build WhatsApp products for the Android and BlackBerry operating system, respectively. Yet, they remained true to their frugal origins.

The team would share a warehouse with Evernote (who’d later take over the whole building and essentially kicked them out). They would wear blankets to keep them warm and used the cheapest Ikea furniture for work.

What became more abstruse was that the team found it necessary to put up an office sign. Instead, they’d tell job candidates to get to the Evernote building, walk around the back, find the unmarked door, and simply knock.

A bigger problem became the startup’s largest cost pool: SMS verifications. SMS brokers like Click-A-Tell would send the messages on WhatsApp’s behalf and charge them anywhere between $0.02 to $1 depending on location.

The team would occasionally change the app’s pricing structure from free to paid (equal to $1) to cover its cost. Yet, despite the fact that they charged users, WhatsApp would rise to become a top 20 app in the U.S. App Store by the beginning of 2011.

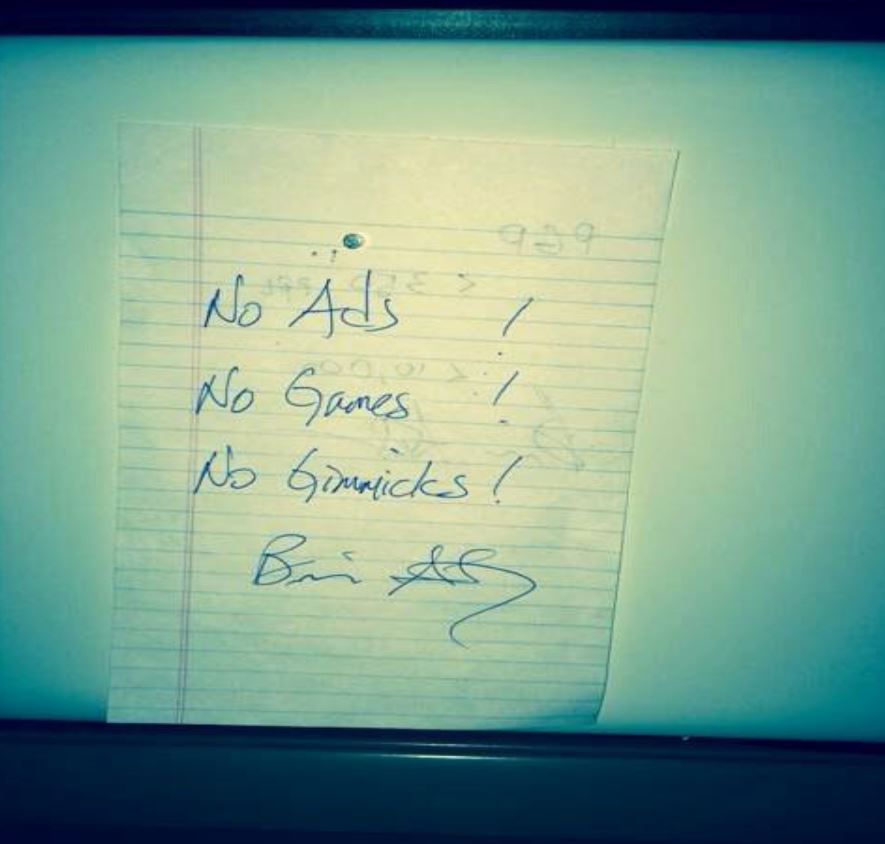

WhatsApp’s growth was solely based on word of mouth and the quality of the product they delivered. Deeply affected by their experience at Yahoo, the founders promised themselves to never derail the app with ads or other distractions. To that extent, Koum had a note in front of his desk reminding him of the exact same thing.

Being on top of the App Store world and building a high-quality product put the team on the radar of a lot of Silicon Valley investors. Yet, they were rejected right from the start. Acton’s fear, at the time, was that VC funding would lead to lesser decision-making power – and investors would force them to insert ads into the application.

One investor proved to be particularly enduring. Jim Goetz, Partner at Sequoia Capital, tried to get in contact with the founders for well over 8 months – without any success. Eventually, his persistent follow-ups led to a meeting at the Red Rock Café, a famous Mountain View workspace known to be home to many startup founders.

Goetz ensured the duo that he’d only act as a strategic advisor and not force them to make any business decisions they weren’t comfortable with. In the end, Sequoia was able to lead WhatsApp’s Series A round, which netted the company $8 million in additional funds.

The founders made sure to use the money to the best of their ability. By 2013, WhatsApp had over 200 million monthly active users and a staff of 50 people. Sequoia would go on to invest another $50 million during WhatsApp’s Series B, which valued the company at $1.5 billion.

Ironically enough, when Goetz signed the check, Acton sent him a screenshot of the firm’s account balance, which was equal to $8.2 million. They simply needed the money ”for insurance”, as Acton recalled.

Being a highly capital efficient company with a rapidly expanding user base does eventually put you on the radar. In the spring of 2012, Koum’s email inbox was hit with the following subject line:

“Get together?”

The sender was no one other than Mark Zuckerberg asking the WhatsApp founder to have a chat over dinner. Over the next year, the pair got together for many more of these dinners, discussing the chances of a potential acquisition.

In mid-June 2013, when WhatsApp just crossed the 300 million user mark, the founders had a scheduled meeting with Google’s Head of Android Sundar Pichai (who now serves as the company’s CEO).

Pichai would even introduce the pair to then Google CEO and co-founder Larry Page. A few days before that meeting was bound to happen, a WhatsApp employee ran into Amin Zoufonoun, Facebook’s Director of Business Development and one of the brains behind the $1 billion Instagram acquisition.

He told him that Acton and Koum were supposed to meet Page in the next few days. Zoufonoun immediately went back to the office to speed up the acquisition process in order to avoid a last-minute counteroffer by Google. Yet, the founders still attended that Google meeting but actually didn’t even receive an offer from the search giant.

About 2 weeks after that meeting, on February 15th, 2014, Zuckerberg and Koum inked the deal. Facebook would pay $19 billion to acquire 100 percent of WhatsApp, paying $4 billion in cash, $12 billion in stock, and another $3 billion in stock grants if the founders would stay on at Facebook for at least 4 years. The price ended up rising to $22 billion due to the share-based components of the deal.

To make this even more of a Cinderella story, Koum signed the agreement on the doorsteps of his old welfare home in Mountain View.

Furthermore, the deal would make Koum and Acton overnight billionaires. Koum would make $6.8 billion after taxes while Acton would pocket $3 billion. Lastly, Sequoia walked away with $3.5 billion, which represented a 60-fold return on the firm’s $58 million investment.

Ironically enough, both Acton and Koum applied for roles at Facebook after they left Yahoo but were ultimately rejected. Now, they had not only a seat at the table but access to quasi-infinite resources. As a result, WhatsApp was able to triple its user base to 1.5 billion within 3 years of the acquisition.

On the outside, everything was looking great but the tension between Facebook and WhatsApp executives began to rise soon after.

Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s Chief Operating Officer at the time, as well as many other Facebook executives started to push WhatsApp’s founding team to ease the end-to-end encryption it became known for.

Furthermore, they wanted to include targeted ads within the app, a concept that both Acton and Koum opposed heavily (they even had a clause in their contracts that granted them accelerated payouts if Facebook insisted to include ads).

A few disagreements between the company’s employees also popped up. For instance, Facebook employees issued their dissatisfaction about the fact that WhatApp’s desks, which were brought over from their Mountain View location (WhatsApp moved into Facebook’s headquarters after the acquisition), were larger than the standard desks Facebook employees were equipped with.

WhatsApp also negotiated for nicer bathrooms and had conference rooms which permitted Facebook employees from entering.

WhatsApp, on the other end, wasn’t without fault either. When the founders were tasked with replicating Snapchat’s Story feature, which was a key differentiator of its growth model, into WhatsApp, Acton and Koum used that assignment as an excuse to delay exploring other revenue-generating avenues.

Eventually, the mounting tension between the two camps became irreparable. On September 17th, 2017, Acton announced he would leave WhatsApp. Koum’s departure came just seven months after (in April 2018). Due to their premature exit, Acton and Koum gave up $900 million and $400 million in stock compensation, respectively.

To make matters worse, Acton publicly denounced Facebook, criticizing the company on how it handled its user data in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal. He even pushed people to stop using Facebook by publicly supporting the #DeleteFacebook movement.

Facebook, that same year, was even slapped with a $122 million fine by the European Union due to providing “incorrect or misleading information” in regards to the acquisition.

While all these incidents painted a gloomy picture of how miserable life as a Facebook-owned property can be, it did not seem to affect WhatsApp’s usage growth at all. Particularly India, with its 1.37 billion inhabitants, became one of the major growth markets.

WhatsApp’s popularity among Indians allowed many businesses to flourish by offering products and services to millions of smartphone users via the app’s Business tools. Unfortunately though, just like its mother company, WhatsApp became a breeding ground for spreading fake news.

In 2017, 17 men were killed after false rumors of their attempts to kidnap kids from a village spread on the app. WhatsApp introduced various measures, such as limits on message forwarding and full-page newspaper ads warning about these rumors, to combat the spread of fake news on its platform.

In some instances, WhatsApp (albeit unintentionally) even caused political leaders to be ousted. In October 2019, Lebanon’s Prime Minster Saad Hariri, amidst intense public pressure, was forced to resign from his position after proposing a 20 percent tax on the first WhatsApp call users made in a day.

And the bad news did not end there. In January 2021, WhatsApp announced that it would roll out a new privacy policy which forced users to share data with its parent company Facebook.

While it turned out to be a misunderstanding (Facebook already gathers WhatsApp data in an encrypted way, so user information remains private), the damage was already done.

Many of its users flocked to other messaging platforms, such as Signal (as promoted in a tweet by Elon Musk), Telegram, or Viber. Initially, the company said it would remove users who wouldn’t accept the new terms. However, the company reversed its course days before the supposed go-live on May 15th, 2021.

In fact, the company has now doubled down on privacy-related changes and other features that often mimic those of Telegram and such. For instance, in June, the platform introduced multi-device support, which allows users to message on various devices at the same time. Other features include encrypted video chats as well as disappearing photos and videos (August 2021).

Unfortunately, not everyone seemed to believe in WhatsApp’s noble intentions. In September 2021, Irish authorities imposed a €225 million (~$267 million) fine on WhatsApp for failing to tell some users how much data was shared with Facebook. The fine was the second highest ever issued under Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which was first introduced back in May 2018.

WhatsApp, a a result, updated its privacy policy for users in Ireland and Europe in November. Two months later, in January 2022, WhatsApp rival Signal announced that co-founder Brian Action would serve as the messenger’s interim CEO.

Today, WhatsApp is widely considered to be the world’s largest communication platform. Over 100 billion messages are now being exchanged on the platform – every day. WhatsApp currently employs well over 1,000 people in 6 office locations across 4 countries.

How Does WhatsApp Make Money?

WhatsApp makes money by charging companies for access to its Business API as well as transaction fees from payments.

But before we go into more detail, let’s take a closer look at the firm’s previous monetization efforts.

As earlier stated, WhatsApp used to monetize its customers via a subscription model. Users paid $1 per year to be able to use the app. That would be equal to a $2 billion revenue run rate given WhatsApp’s 2 billion user base.

In 2016, 2 years after the acquisition, Facebook decided to ditch the $1 fee. The underlying strategy was to continue focusing on user growth and help WhatsApp become the ubiquitous leader in the messaging space.

That also meant ditching any plans to insert ads into the product. Whilst Facebook’s Messenger product does offer in-app advertising, its executives have decided to work with businesses to monetize WhatsApp.

Facebook, now known as Meta, has since rolled out various services to monetize WhatsApp. Let’s take a closer look at each of WhatsApp’s monetization channels.

Business API

In 2018, WhatsApp launched its Business API, which became the first continuous effort to monetize the app post-acquisition.

Business are charged on a per-message basis. However, the first 24hrs of a conversion incur no cost. Every message after that 24-hour window costs anywhere between $0.0085 and $0.0058 per message – depending on the total message volume and country of jurisdiction.

The first 1,000 conversations each month come at no cost. Those conversations can either be initiated by the user or business itself. A user-initiated conversion is substantially cheaper than if a business starts one.

The 24-hour limit is supposed to encourage businesses to improve and speed up their reply time. This, in turn, increases the customer’s satisfaction and thus improves the likeliness of both parties (customer and merchant) to continue using WhatsApp.

Furthermore, WhatsApp partners up with other companies, such as the cloud communication platform Twilio, to deliver its API.

Meta CEO Zuckerberg, during a company-related event in May 2022, announced that WhatsApp is working on expanding the functionality of its Business API.

Features in development include the option to monitor ongoing chats across 10 devices and enable click-to-chat links that businesses can adjust and post on their own websites.

Payment Fees

WhatsApp has been working on a payment product since 2018. In June 2020, it finally launched a payment service in Brazil that allowed users to pay each other (mirroring Venmo and Zelle) as well as other businesses on the platform.

Unfortunately, around 10 days later, Brazil’s central bank suspended the launch, stating that it wanted to “preserve an adequate competitive environment” within its mobile payments industry. Mastercard and Visa, WhatsApp’s payment partners, were asked to suspend any money transfer within the app.

While the failed launch was a tough pill to swallow, it hasn’t stopped the company from pursuing the payment concept.

In November 2020, it enabled P2P payments in India, the firm’s largest market by user count. Business payments, in which WhatsApp would receive a portion of the order value, are expected to follow in the next few months. Also, in May 2021, Brazil lifted its payment ban, adding another country to the mix.

Luckily, sending payments to one of your friends or family members remains free of charge. WhatsApp monetizes its payment feature on the business side.

Whenever you pay a merchant using WhatsApp Pay, that business is being charged with a 3.99 percent transaction fee.

Currently, 100 million users in India are allowed to use the product. The National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) continues to put a cap on the number of users WhatsApp can onboard, which is expected to increase over time.

Users are, furthermore,, incentivized to use the service through cashback rewards. Whenever someone pays a merchant via WhatsApp Pay, he or she will receive a cashback reward of up to $0.40.

WhatsApp Funding, Valuation & Revenue

According to Crunchbase, WhatsApp has raised a total of $60.3 million across 3 rounds of venture capital funding.

The company’s only investor throughout its startup time was Sequoia Capital, with partner Jim Goetz leading negotiations.

The last time WhatsApp valuation was publicly disclosed occurred during its acquisition by Facebook. The tech giant paid a whopping $19 billion to acquire a 100 percent stake in the company.

Facebook has furthermore decided to not disclose any revenue it generates from WhatsApp. Instead, any revenue figures are included in the firm’s overall income figures.