Netflix has achieved what very few companies on this earth have done before: it has become synonymous with a whole category.

While Netflix wasn’t even the first streaming service (that title goes to Hong Kong-based iTV, which launched in 1998), it certainly is by far the most beloved.

And although recent subscriber losses and heightened competition have called into question how long it can maintain its dominant position, the company possesses several strengths that should allow it to maintain its dominant position.

In short, Netflix possesses three distinct competitive moats, namely scale economies, branding, and counter positioning.

We will be analyzing Netflix’s competitive advantages through the lens of Hamilton Helmer’s 7 powers, which detail how companies are gaining an edge over their contemporaries.

World-renowned tech executives, which include Netflix founder Reed Hastings and Daniel Ek (CEO and founder of Spotify), have leaned on Helmer’s framework to devise the strategy for their respective businesses. In fact, Hastings even published the foreword to Helmer’s book.

The 7 powers are: scale economics, switching costs, cornered resource, counter positioning, branding, network effects, and process power.

However, I will only analyze the powers that are applicable to Netflix’s business. Scale economies, for example, are normally how manufacturing companies producing physical components separate themselves from the pack.

So, without further ado, let’s take a closer look at each competitive advantage that Netflix possesses.

1. Branding

One of Netflix’s core competitive moats is the brand equity it has been able to amass over the past decades.

The first indication of its brand strength is the valuation that the company has been able to amass. Netflix is the second highest-valued pure-play media brand behind Disney, with the latter also deriving revenue from its parks, merchandise, and associated brands like Hulu and ESPN.

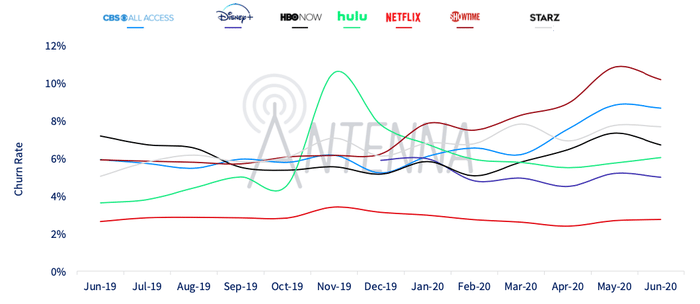

An added data point that supports the notion of a strong brand is Netflix’s comparatively low churn rate. According to Antenna Analytics, Netflix ranks first among streaming platforms with a churn rate of around 2.4 percent.

In all fairness, that metric has since increased, mainly as a result of heightened inflation, the removal of Russian subscribers due to the war in Ukraine, and overall greater competition. In early 2022, Netflix even lost subscribers for the first time during its existence (200,000) but rebounded swiftly in the next quarter.

Another way with which we can measure the brand strength of Netflix is the Net Promoter Score (NPS), a common metric that indicates how many fans and detractors a given service has.

Subscription Flow estimates that Netflix’s NPS is equal to 51 while Disney Plus hovers around 42 and Hulu scores a mere 21.

Pricing power is yet another means through which we can measure a brand’s popularity. Netflix’s standard plan in the United States currently costs $15.50 per month. In comparison, this is how much other streaming services charge for similar plans:

- Disney+: $7.99/month

- Hulu: $14.99/month

- HBO Max: $14.99/month

- Paramount+: $9.99/month

- Peacock: $9.99/month

- Amazon Prime: $14.99/month

- Apple TV+: $6.99/month

Now, to be fair, some of those competitors severely under-price their offerings in hopes of attracting more subscribers. Furthermore, in the case of both Apple and Amazon, the two tech giants are not in the streaming business to turn a profit but attract even more customers to their core businesses.

Consequently, charging the highest prices yet having the lowest churn is pretty indicative of the brand strength that Netflix possesses. This is particularly impressive given that Netflix’s subscription can be canceled at any time.

Additionally, Netflix is one of the only streaming platforms in the United States that does not offer (discounted) yearly plans, so there are no lock-in effects that it creates, which makes the low churn rate that much more impressive.

Netflix’s brand equity has, furthermore, enabled the firm to amass the largest subscriber base of any streaming service in the world – directly tying into Netflix’s second competitive advantage.

2. Scale Economies

The second competitive advantage is the scale economies that Netflix has reached. Helmer defines scale economies as follows:

“A business in which per unit cost declines as production volume increases.”

Scale economies are traditionally prominent among manufacturing companies. For example, the more vehicles BMW produces, the cheaper each vehicle becomes as the company invests in technology and process optimization.

Interestingly though, scale economies apply to subscription-based companies like Netflix as well. When Netflix pivoted to become a streaming platform (more on that in the next chapter), it did so by signing a content licensing deal with cable TV provider Starz for $30 million a year.

Now, this obviously represents a fairly significant cost base in and of itself. However, the deal and the content that came with it became a huge factor as to why Netflix was able to increase its subscriber base from around 9 million to around 25.7 million when the deal expired in 2012.

As a result, the per-unit cost of the fixed licensing fees that Netflix was paying decreased drastically due to the onslaught of new subscribers that it helped to attract. Licensing content at a fixed rate, therefore, became one of Netflix’s biggest competitive moats.

Meanwhile, competing platforms like Hulu weren’t able to pay those same fixed fees because their subscriber base wouldn’t warrant such expenditures. Netflix, after all, still had a lucrative DVD rental business that was bringing in $1.25 billion in revenue in 2007 alone.

Unfortunately, as more and more traditional media companies began to realize how lucrative streaming could be, they either began to substantially increase fees (thus making it economically unfeasible to license content) or took the content off altogether to launch their own streaming platforms.

Nevertheless, the scale economies that Netflix initially benefitted from still apply to this day. The firm currently boasts over 220 million subscribers, leading to annual revenues of almost $30 billion in 2021 alone (while having over $6 billion in cash on hand).

Therefore, Netflix’s baseline of being able to invest in content is comparatively higher. Amazon and Apple can certainly keep up with that spending but questions of monopolistic abuse continue looming over their heads. The only content-oriented company that boasts a similar budget is Disney.

For reference, the mouse spent a whopping $25 billion on content in 2021, which also includes costs such as sports rights. Netflix, on the other hand, invested $17 billion over that same time span.

Now, where Netflix separates itself from the pack is content velocity. The company, in search of the next Stranger Things, is able to churn out substantially more content at a much lower average cost.

Disney, for example, spent $15 million per episode on The Mandalorian while many of its Marvel shows, such as WandaVision, would cost as much as $25 million per episode. Amazon even spent as much as $55 million per episode on The Rings of Power.

While Netflix did commit $30 million per episode for the fourth season of Stranger Things, it did so after carefully testing the format ($6 million per episode for season 1 of Stranger Things, in this case).

However, this may also alienate users as Netflix has been known to prematurely cancel shows that don’t perform too well.

Another aspect where its scale economies come into play is internationalization. Only a third of its total subscriber base is actually situated in North America, with the rest being spread across the globe.

In fact, Netflix is available in more than 190 countries across the globe. Many of its competitors are either not serving foreign users, only available in a handful or dozens of markets, or not localizing their content to account for local preferences.

And localization is a key strength that separates Netflix from many of the other streaming platforms. Take, for instance, its hit title Squid Game, which cost the company reportedly $21.4 million to produce but brought in almost $900 million in impact value while garnering 111 million views globally within one month of launching.

Other examples that led to outsized returns for Netflix include hit shows like Money Heist (Spain), Dark (Germany), and Lupin (France), among many others. The firm views this content as not just local-for-local, but also local-for-global. This means hit shows like Squid Game not only bring in subscribers in local markets like South Korea but from all across the world.

Apart from vastly expanding its total addressable market (TAM), the single biggest advantage of Netflix’s internationalization strategy is the cost of content production, which is significantly lower outside of the United States.

The company has set up regional headquarters in a variety of continents (such as Europe and Asia), on top of acquiring foreign production studios or opening them itself. In Spain, for example, it has set up the Tres Cantos hub where it produced 30 movies and TV shows in 2022 alone.

Netflix also invests heavily in dubbing to accommodate viewers in countries like Germany, Italy, and Spain where consuming content in the local language is preferred. More precisely, Netflix is partnering with more than 200 dubbing studios across the globe to produce dubbed versions of all of its content.

As a result of its localized content production strategy, the share of originals on Netflix has vastly expanded in the past few years. While 79 percent of its content was licensed in 2019, that number shrank to 66 percent by the end of 2021 – and is only continuing to decrease.

And although the upfront cost of creating that content may be steep, it allows Netflix to save on licensing fees, which remains one of its largest cost centers. And the less it spends on content licensing, the more it can invest into production, which (if the content is great) should bring in more subscribers.

With that being said, let’s take a look at the last competitive advantage that got Netflix where it is today.

3. Counter Positioning

The last competitive advantage is one that may not necessarily apply to Netflix anymore but was key in the company’s early days.

Helmer defines counter-positioning as follows:

“A newcomer adopts a new, superior business model which the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business.”

Interestingly, Netflix successfully applied counter-positioning two times throughout its existence. The company initially began as a DVD-by-mail business and largely competed against the likes of Blockbuster, which had amassed a vast store network from where they could serve customers almost instantly (at least based on customer expectations in the 1990s).

However, Blockbuster began to abuse its market-leading position by imposing hefty late fees on customers that missed their DVD return dates. Those late fees were making up a considerable portion of the revenue that Blockbuster generated.

In fact, Hastings has credited the hefty late fees as the inspiration for starting Netflix. After returning a copy of Apollo 13, he was charged a late fee of $40.

And since Blockbuster went public in August 1999, it couldn’t just tell public market investors that it would get rid of one of its biggest revenue drivers as the stock would’ve cratered (especially with the bursting of the dot-com bubble 2 years later).

Additionally, Blockbuster was also making money from selling concessions at checkout, so shifting to a DVD mailing business would’ve diminished yet another key income source.

So, when Netflix introduced its DVD-by-mail business in March 1998, it not only offered a better consumer experience but also did not impose late fees on customers. The rapid adoption of the internet and personal computers further contributed to its explosive growth.

Another part of Netflix’s counter-positioning was the business model strategy it adopted. Instead of charging consumers for every DVD, it allowed them to subscribe for $19.95 per month to receive as many copies as they wished.

And the rest, as they say, is history. Ironically, Blockbuster, due to the bursting of the internet bubble, had the chance of acquiring Netflix for $50 million but Blockbuster CEO John Antioco ultimately refused.

When Blockbuster finally launched its own DVD rental business in 2004, it was simply too late. And Netflix? Well, CEO and founder Reed Hastings was already working on one of the greatest pivots in business history – and the second example of successful counter-positioning.

By the mid-2000s, broadband costs were rapidly declining to the point that video consumption over the internet became a viable opportunity. This also led to the emergence of startups like YouTube, which was quickly scooped up by Google.

Netflix had already built the muscle to be taking advantage of that trend, for instance, vis-a-vis its CineMatch algorithm. It would analyze three factors, namely Netflix’s whole movie catalog, the ratings that subscribers gave to movies they had consumed, and the combined ratings of specific titles from all Netflix subscribers, to devise a somewhat accurate recommendation.

Being able to make more accurate recommendations significantly decreased subscriber churn, which would consequently boost the firm’s bottom line in anticipation of its upcoming pivot. That notion was supported by CEO Hastings who had this to say during an earlier earnings call:

“Our strategy for achieving online movie rental leadership is to continue to aggressively grow our DVD subscription business and to transition these subscribers to Internet video delivery as part of their Netflix subscription offering.”

So, although the DVD rental business was growing at a rapid pace, Hastings knew that streaming would be the dominant medium with which people consume content. However, the early signs were already there. In 2007, for instance, the DVD market shrank by 4.5 percent – the first time in history that sales had fallen.

So, in 2007, Netflix introduced its streaming service Watch Now with more than 1,000 titles. And just months later, the company disclosed that it would stop DVD retail sales while simultaneously partnering with cable TV network Starz, adding another 2,500 movies and TV shows to its slate.

By the time (2012) Starz realized what it had done and thus decided to cancel its licensing deal with Netflix, it was already too late. At that point, Netflix had tens of millions of subscribers and would soon even launch its first original programming with Lilyhammer and House of Cards.

With streaming, Netflix once again counter-positioned itself. In this case, it was against the various cable TV networks. Cable, for the longest time and much like the newspaper industry, enjoyed preferential consumer access.

They essentially acted as monopoly franchises in localities and essentially forced consumers to pay for bundles of channels – many of which weren’t even relevant to their preferences.

Plus, the contracts that people signed couldn’t just be canceled at any time. Instead, they were often tied to those payments for at least a year or two.

Expensive monthly bundles weren’t their only money maker, though. Cable networks would also derive a substantial amount of money from advertising. CBS, for example, generated a whopping $6.5 billion in ad-based revenue alone during 2010.

Once again, Netflix counter-positioned itself against the cable incumbents. For once, it offered a fairly affordable monthly subscription that, more importantly, could be canceled at any time.

However, with an ever-increasing content catalog, which also included hit shows like The Office or Friends (licensed from those very same cable networks), consumers had little incentive to cancel.

Meanwhile, the cable networks also didn’t react to the looming threat because they themselves were also deriving additional revenue from the licensing fees that Netflix paid them.

Another way in which Netflix counter-positioned itself against cable TV was the 24/7 availability of content. On TV, consumers only had a set time when they could consume an episode.

Additionally, the viewing experience was completely uninterrupted, meaning there weren’t any ads that consumers had to sit through.

And once Netflix expanded into original programming, it did so by encouraging binge-watching and thus releasing all episodes at once. With traditional TV, viewers would have to wait for at least a week until they could see the next episode.

Over time, Netflix’s counter-positioning advantage began to erode as more and more cable networks, such as Disney, NBC, and Paramount, launched streaming services of their own (while taking their most valuable content off of Netflix).

Interestingly, Netflix even suffered from counter-positioning by other services. Some of its fiercest competitors, including Hulu or Peacock, all introduced ad-supported tiers to capture more price-sensitive consumers.

Netflix, for the longest time, refused to add advertising to continue offering an uninterrupted viewing experience. However, in November 2022, it finally gave in.

It remains to be seen whether the company can reinvent itself once again and create sustainable competitive moats.