Executive Summary:

LimeWire was a peer-to-peer file-sharing program that allowed its users to download and upload music in the form of MP3 and other file formats.

LimeWire was shut down in October 2010 as a result of a legal battle between the company and the Recording Industry Association of America. The company rebranded back in May 2022 and launched as a marketplace for NFTs.

Launched in the year 2000, LimeWire grew to become one of the world’s most prominent file-sharing programs. At one point, its software was installed on 18 percent of all computers in circulation.

What Was LimeWire?

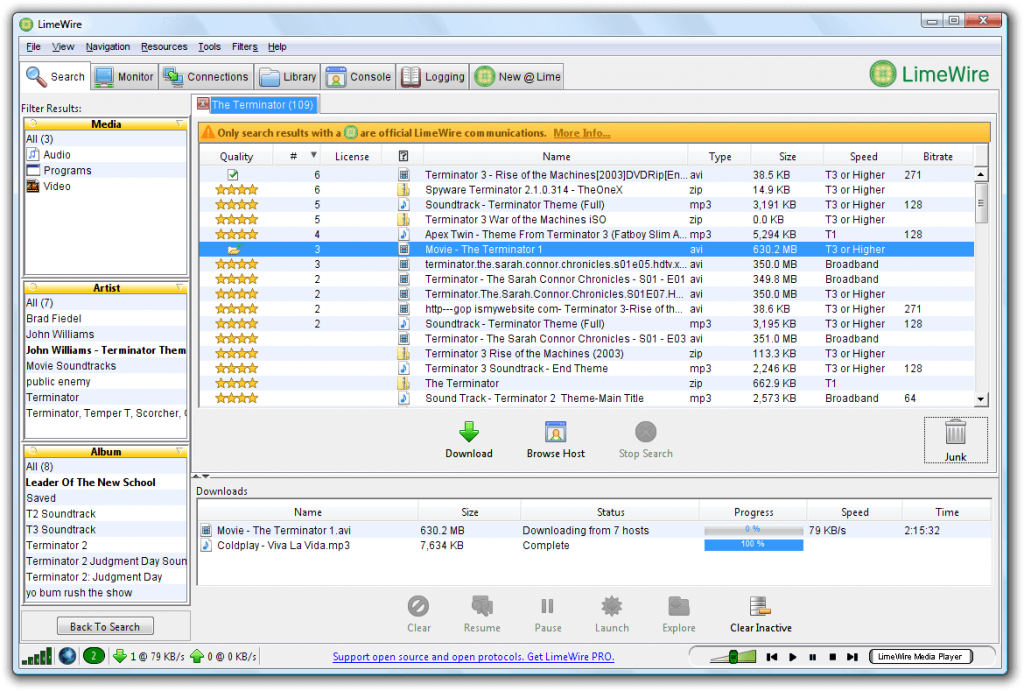

LimeWire was a peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing program that allowed its users to download and upload files through desktop software.

The software could be downloaded and used on devices that had Windows, macOS, Solaris, and Linux installed.

LimeWire was based on Gnutella, which is a network protocol that allows individual machines to interact with each other.

Users could then download and upload a variety of file formats, including MP3 (for music), AVI/MPEG (video), JPG (images), and more.

In order to use LimeWire, users had to first download the software via its website or any other third-party website (such as CNET).

Then, you would go on and open the file that launches the Installer Wizard. After completing the installation, users would have to select which local folders (on their computers) should contain LimeWire files.

Lastly, you would give LimeWire permission to bypass any firewall software. Once they opened the software, users could simply search for any file they wanted to download to their computer.

LimeWire was available at no cost. If users wanted to up their download speeds and search results as well as receiving access to tech support, they could opt into LimeWire Pro for a yearly fee of $21.95.

LimeWire was eventually shut down in October 2010 after a long-lasting legal battle with the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) – a battle we’ll explore closer in the next chapter.

What Happened To LimeWire?

LimeWire, operated by Lime Wire LLC and headquartered in New York City, was initially released on May 3rd, 2000.

The software is the brainchild of Mark Gorton, who himself came from a finance and engineering background. Gorton earned electrical engineering degrees from Yale and Stanford, respectively, and then moved on to work for a defense contractor.

In 1991, he enrolled at Harvard Business School to pursue an MBA, which he wrapped up two years later. Over the course of the next five years, he worked for various Wall Street-based companies, including Credit Suisse and First Boston.

In 1998, Gorton made his first foray into entrepreneurship by founding Tower Research Capital, a hedge fund that utilized quantitative trading and investment strategies. He even incorporated a separate entity called Lime Brokerage which created high-frequency trading software to place trades.

Around the same time, the P2P file-sharing craze slowly begun to take off as more and more people gained access to computers and the internet at large.

The most prominent of the bunch was Napster, which launched in the summer of 1999. Napster had amassed millions of users within a matter of months, at one point even making it one of the most frequented websites in the United States.

Nevertheless, Napster began facing legal troubles almost as soon as it launched, which ultimately led to its demise (you can read more about the company by checking out the link above).

Gorton decided to capitalize on the P2P craze by launching a service of his own. He recruited a variety of technology experts, including Greg Bildson (who joined LimeWire as its CTO), to build out the technology.

LimeWire was initially released in May 2000 – without much public attention. Gnutella, the protocol that LimeWire was built upon (and which just launched months prior), was gaining so much popularity that its network simply became overwhelmed, which led to download speeds being extremely slow.

One of the major things that set LimeWire apart was a feature called heartbeat ping and heartbeat pong. It allowed the network to reorganize itself so that heavy traffic nodes would connect with other heavy traffic nodes while the slower connections would be unaffected. That meant if the connection didn’t respond, they would simply drop it.

Furthermore, LimeWire was troubled by demand simply outstripping available supply. There were only a few clients available on its network while demand for downloads was substantially higher.

The tide eventually turned when Napster was forced to shut itself down on July 1st, 2001. Many of its existing users eventually began using LimeWire for a variety of reasons.

For once, LimeWire was less aggressive in displaying ads within its software than some of its competitors at the time, which included BearShare, Morpheus, and KaZaA.

Second, many of those competing platforms hosted files that contained viruses. LimeWire had built tools that were scanning files more rigorously, thus offering a much safer experience.

By the end of 2001, LimeWire had attracted millions of users to its software. Over the coming years, it continued to release product improvements while growing in popularity. In 2005, one of its biggest competitors, Grokster, was forced to shut down. Consequently, the majority of Grokster’s users migrated to LimeWire.

As a result of its growing popularity, LimeWire was able to grow its annual revenue from $6 million in 2004 to over $20 million in 2006. Its software, at that point, was installed on 18 percent of all computers in circulation. LimeWire essentially became the world’s most prominent P2P file-sharing software.

Despite (or rather because of) its overwhelming success, LimeWire eventually had to face legal consequences as well. In August 2006, the RIAA (which also managed to shut down Napster in 2001) filed a lawsuit against Lime Wire LLC.

The RIAA, which represents the major studios Universal Music, Sony BMG, EMI, and Warner Music Group, stated that LimeWire’s software enabled users to exchange copyrighted music without the label’s consent. RIAA demanded $150,000 for every song illegally traded on the network.

Weeks later, LimeWire’s lawyers filed a countersuit, alleging that the studios refused to license their music to LimeWire to put it out of business. Obviously, LimeWire also denied any wrongdoing.

A year after the lawsuit was made public (in August 2007), LimeWire announced that it intended to launch a digital music store (much like iTunes). The store, which would be a standalone website, would allow customers to purchase individual songs for a one-time fee.

Meanwhile, a federal judge tossed its claims against the RIAA, stating that it had provided more than a million pages of documents and 100GB worth of data to support its case.

LimeWire, in turn, had “not yet identified any additional facts it would plead that would enable it, for example, to demonstrate the existence of a conspiracy” against its business.

Finally, in March 2008, LimeWire unveiled the beta version of its music store. The digital store, which was only available to U.S.-based customers, offered a catalog of 500,000 songs from independent labels on either a pay-per-track or monthly subscription basis. The major labels, as expected, did not join the service.

Later, in July, LimeWire entered the news cycle once again – this time not over copyrighted music, though. The personal data of Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer was stolen from his computer and made available for download on LimeWire.

Subsequent reports and TV documentaries revealed other sensitive information that was being shared on LimeWire. For instance, more than 150,000 tax returns and almost 626,000 credit reports were uploaded on its network for download.

Mark Gorton, who by that time had become the firm’s chairman (while George Searle led the company as CEO from 2007 onwards), even sent a letter to congress, assuring that LimeWire would add certain features to prevent the sharing of sensitive data. For instance, it prohibited the sharing of file types such as .doc, .pdf, or .rtf.

Meanwhile, LimeWire continued to focus on expanding its legitimate store offering. In August 2008, it cut a deal with The Orchard, a large digital distributor for independent artists and small labels, to add another one million song titles to its store.

Unfortunately, not everyone was liking its efforts. In July 2009, LimeWire employees allegedly got into a bar fight with representatives from the music label Dovecote Records.

The real smackdown happened a few months later, though. In May 2010, almost four years after the RIAA filed its initial lawsuit, U.S. District Judge Kimba M. Wood ruled that LimeWire had committed “substantial amount of copyright infringement”. She, furthermore, stated that the company had not taken any meaningful steps to combat the sharing of copyrighted material.

As a result of the ruling, LimeWire allegedly considered to filter out pirated content while trying to strike a deal with the major labels to distribute their music legally. The labels did not bulge, though.

In June 2010, they asked a New York federal court to shut down the platform. Furthermore, the record labels demanded more than $1 billion in compensation for all the songs that had been illegally exchanged on LimeWire.

On July 3rd, 2010, a federal judge rejected a request by the labels to freeze all of LimeWire’s and Groton’s assets. Back in 2005 and beyond, the founder had allegedly moved a substantial amount of LimeWire assets into a family trust to secure them from a potential settlement.

On the 26th of October, 2010, LimeWire’s days as a file-sharing network were officially over. Judge Wood issued an injunction that forced the platform to deactivate “the searching, downloading, uploading, file trading and/or file distribution functionality, and/or all functionality” of its software.

While LimeWire’s goal remained to become a legitimate digital music store, realistically it was a mere drop in the proverbial ocean. None of the major labels, after four years of litigation, would have been willing to work together with the company.

A month after LimeWire was forced to shut down, an unauthorized version called LimeWire Pirate Edition (LPE) emerged – officially without the knowledge of its predecessor.

After mounting legal pressures, LimeWire eventually decided to shut down its music store on December 31st, 2010. A few months later, in May 2011, LimeWire finally settled with the RIAA for a total of $105 million.

Unfortunately for LimeWire, that wasn’t the rest of the story. In July 2011, LimeWire was sued by Merlin, a trade group representing 12,000 indie labels (including artists like Adele), filed a similar lawsuit to the one that the RIAA had just won.

In February 2012, a group of three Hollywood studios, including Disney and Paramount, filed another copyright infringement lawsuit.

While LimeWire settled with Merlin in March 2012 for $15 million, the Hollywood studios eventually dropped their $200 million copyright lawsuit in November 2013.

In the meantime, a former LimeWire developer named Zlatin Balevsky as well as unnamed colleagues purchased the company’s domain back in 2011. For the longest time, when accessing LimeWire.com, one would be able to download MuWire, a similar P2P filesharing service. This all changed in March 2022, though.

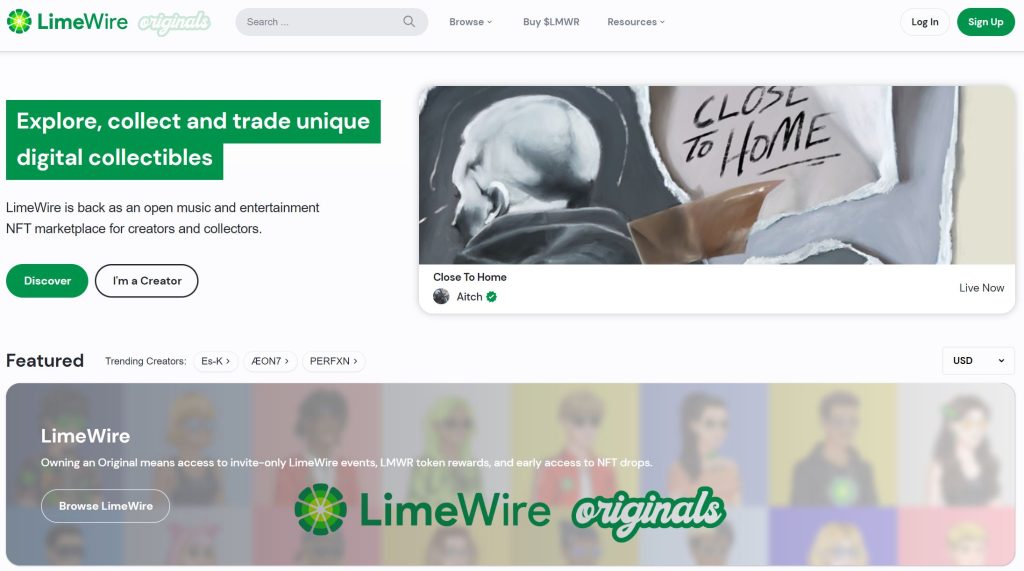

That same month, and twelve years after shutting down, the company announced that it would relaunch as an NFT marketplace in May.

Ironically, the platform now focuses on selling music and entertainment-related NFTs and even agreed to a deal with Universal Music Group to license some of its content.

To get the new business established, the new owners managed to raise $10.4 million via an Initial Coin Offering (ICO) in April 2022. It remains to be seen whether the new ownership can make it work this time around.

By the way, if you feel bad for Gorton, then be assured that he came out just fine. In 2016, he purchased a New York townhouse for $7.55 million. He, furthermore, remained at the helm of his high-frequency trading firm Tower Research Capital, a company with over 1,000 employees, until August 2019.

Why Did LimeWire Shut Down?

LimeWire shut down in October 2011 because it lost its legal battle with the Recording Industry Association of America.

Due to a substantive number of copyright infringement cases, U.S. District Judge Kimba M. Wood ruled that LimeWire had to immediately halt the distribution of any copyrighted materials.

Looking at Napster, which now operates as a legal music streaming service and also tries to establish itself as an NFT marketplace, many believed that LimeWire could’ve gone on to exist if it wanted to.

Apparently, Gorton and LimeWire executives only began reaching out to the major labels regarding the launch of a legitimate service after the initial ruling in May 2010.

This sentiment was further supported by Wayne Russo, a former president at Grokster. In an interview with CNET, he said that they wouldn’t even want to discuss the creation of a legal platform as they thought they were untouchable.

After all, Gorton slowly but surely moved many of his LimeWire assets into a protected family trust. Or to put it in the words of Wayne Rosso:

“He knew what he was doing. The problem is Mark Gorton thinks he’s smarter than everybody else. Certainly, he thinks he’s smarter than his attorneys…I don’t feel sorry for any of these guys. They had plenty of opportunity to do something legitimate. They chose something else.”